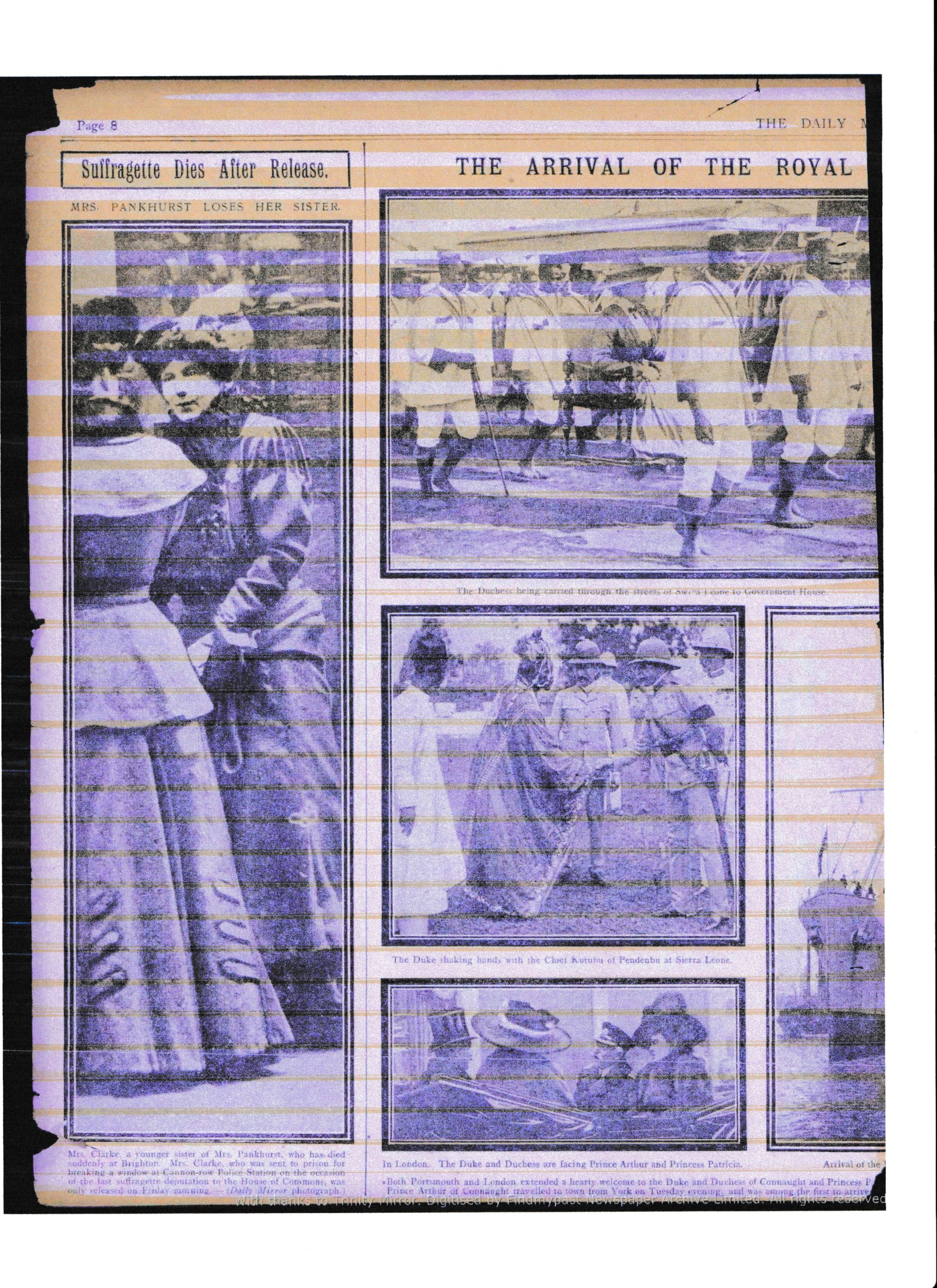

The Hidden History of Mary Clarke – Revised and Updated

This brief history by Jean Calder is also available as a booklet.

Forgotten Sisters

In recent years we have had to re-evaluate the political and cultural significance of statues. There is a recognition that, despite women’s many achievements, hardly any named statues across Britain commemorate them. They have quite literally been hidden from history.

Brighton & Hove is typical. Only one woman has a statue and she is Queen Victoria, commemorated less because of her achievements, than because she was monarch. This is why, in 2018, the charitable Mary Clarke Statue Appeal was set up to commemorate and fund a statue of a woman who served Brighton and Sussex faithfully, but whose extraordinary life and sacrifice had been almost entirely forgotten, not least in Brighton, where from 1909 until her death in 1910 she led the south east suffrage movement.

Mary was the first suffragette to die for women’s right to vote. Brighton and Hove honoured her in late 2024 by posthumously awarding her the Freedom of the City, the only woman currently to hold this honour. Yet there remains no public memorial for her anywhere in the country.

Despite her sacrifice – and the fact she was Emmeline Pankhurst’s sister and co-worker – she is not even included among the fifty-nine suffrage campaigners commemorated on the plinth of the 2018 statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square. The names of her sister Emmeline and her three Pankhurst nieces, Christabel, Sylvia and Adela, are there, but Mary’s name is missing.

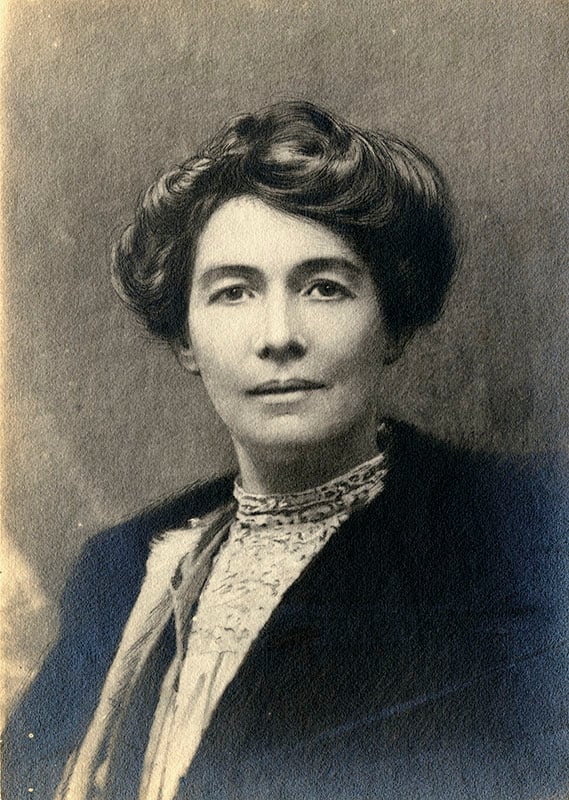

Mary Clarke

Mary Clarke was born Mary Jane Goulden in 1861 in Salford to a radical family. She was devoted to her older sister Emmeline and supported her throughout her life, facilitating her suffrage campaigning and other political activities, as well as those of Emmeline’s husband, the radical lawyer Richard Pankhurst. Mary was politically aware and a member of the Independent Labour Party. She was also a decorative artist, but spent most of her time supporting Emmeline. Mary ran Emmeline’s household, cared for her children, supported her (largely unsuccessful) business ventures and, after Richard’s death, deputised for her work as a paid Registrar of Births and Deaths. Her niece Christabel Pankhurst referred to Mary as their “deputy mother”, and there is no doubt her early organisational and emotional support freed Emmeline and the three suffragette nieces to develop their political ideas and campaigning skills.

Mary was a life-long supporter of women’s suffrage and in 1906, after she escaped a deeply unhappy marriage, became a co-founder of the National Women’s Social and Political Union (W.S.P.U.) along with Emmeline. Thereafter she worked for the Union and in 1909 was appointed Organiser for Brighton and the south east. She was imprisoned three times.

Though Mary was known for her gentleness and was not physically strong, she was extraordinarily brave. At a time when domestic violence was condoned and divorce a matter of shame, she had

escaped an abusive marriage, during which she experienced destitution and homelessness. Thereafter she dedicated her life to the struggle for women’s suffrage. She had no children of her own, but remained a loving aunt to her nieces and nephews and a beloved and respected mentor and leader to younger suffragettes.

A Leader in the Making

Mary was a self-effacing woman who usually avoided the camera and often worked in the background – unlike the charismatic Emmeline, who was a brilliant communicator and adept at using the media. However, Mary was a formidable organiser and in the last decade of her life, grew in confidence, taking centre stage when required.

Mary was one of the speakers at the huge Hyde Park rally, in June 1908, where approximately 500,000 people gathered around twenty platforms. It was a remarkable achievement for a retiring woman who had lived in the shadow of her beloved sister and whose confidence had been undermined by marital abuse and neglect.

Days later she attended a large rally in Parliament Square which was brutally suppressed by around 2,000 police, many of them mounted. It was there she was arrested for the first time for nothing more than peacefully attempting to petition the Prime Minister, an ‘offence’ for which, as Emmeline bitterly noted, a man would almost certainly not have been arrested. She served one month in prison.

We know that by 29 January 1909 Mary had enough confidence to head a delegation of four women to Downing Street, for a similar purpose, and once again this led to arrest and imprisonment. Fellow prisoners commented on her courtesy and gentle dignity, and several gratefully noted her ability to raise morale and encourage others.

Mary was daunted by being appointed W.S.P.U. Organiser in Brighton, fearing she would not be capable of the task. In fact, she triumphed in the role, effectively developing the W.S.P.U. and speaking at many meetings. She may not have been robust, but she was determined and extraordinarily hardworking.

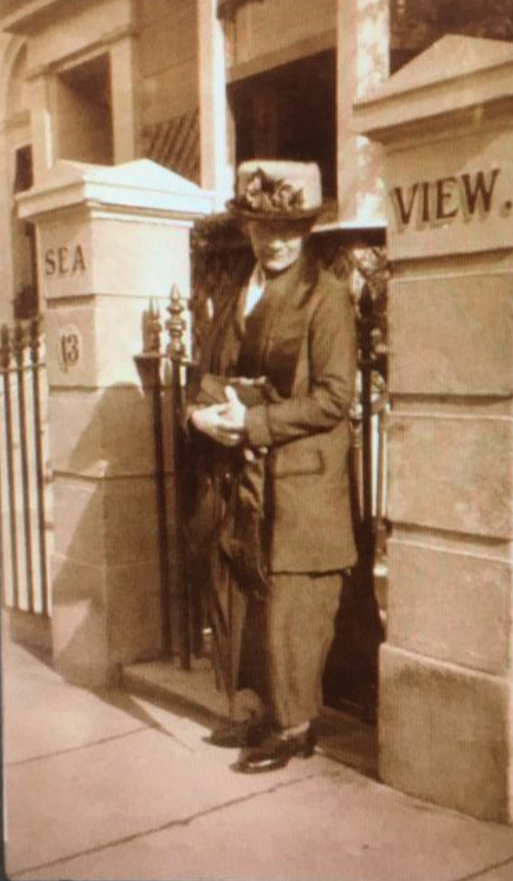

Mary in Brighton & Hove

During her tragically short eighteen months as Brighton Organiser (from June 1909 – December 1910), Mary lodged with local suffragette Minnie Turner, in her boarding house ‘Sea View’ at 13/14 Victoria Road. From this address and the W.S.P.U. office at 8 The Quadrant near Brighton’s Clock Tower, she helped build the W.S.P.U. operation across the South East of England, setting up and supporting many branches. She also organised the two 1910 General Election suffrage campaigns.

Mary spoke to sometimes hostile crowds on the Brighton seafront on an almost daily basis and was reported to handle what Sylvia Pankhurst called “Brighton rowdies” with calm good humour and wit. Suffragette Joan Dugdale recalled how each evening she would address several hundred members of the public, whom she said “admired her pluck”. A local solicitor, who opposed female suffrage, would turn up

each evening to heckle her. Joan recalled “Mrs Clarke never got impatient or angry and managed to silence him by turning his own words against him in a very clever manner.” She spoke admiringly of Mary’s “superhuman” strength of spirit and her gentleness. This ability to handle crowds with calm good humour was reported with admiration by the local press.

Mary also organised and spoke at high profile local public meetings. On 23rd October 1909, Mary chaired a meeting at Hove Town Hall at which Lady Constance Lytton spoke. Constance Lytton had met Mary in prison earlier that year and became one of her greatest admirers. Mary organised many meetings in The Dome and, on 5th May 1910, she chaired and spoke at a major public meeting there, alongside Lady Emily Lutyens and the Reverend Chapman. The local Argus newspaper quoted Mary’s wry comment that “she hoped that as comets were supposed to synchronise with great events, Halley’s comet this year would accompany emancipation of women”.

Mary never achieved Emmeline’s oratorical brilliance, but by the end of her life, this shy woman’s speeches were described by Christabel Pankhurst, as both “eloquent” and “inspirational”.

Resisting Violence and Facing Prison

It must have been difficult for a woman who had experienced abuse to deal with aggressive male opponents. However, Mary’s courage and self-control were legendary. Suffragette leader Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence recalled an occasion in Brighton on which Mary’s path was blocked by a mob of opponents. The hostile men slunk away after she quietly pulled out a copy of the W.S.P.U. newspaper Votes for Women and started to read it as though she were in “a drawing room”.

She was, as her niece Christabel Pankhurst later wrote, “… gentle and selfless as ever, yet brave as a lion – and wonderfully eloquent too.”

Mrs Pethick-Lawrence recalled: “She was on several occasions very much knocked about, and some of her young workers were inclined to strike out in her defence, but she always restrained them.”

Mary never took part in or condoned violent resistance, but she would bravely intervene if others were being attacked. Joan Dugdale described an event in Bournemouth where she, Clara Mordan and Mary were violently heckled and had rotten apples thrown at them. Mary managed to escape from the mob, but saw that Joan was being attacked. She returned to help and “then came in for her blows and kicks and shoving”. Another witness recalled that the hecklers were shouting: “Throw her over a cliff!” Things were so bad by 1910 that Mary was driven to say: “Prison is the only place for self-respecting women.”

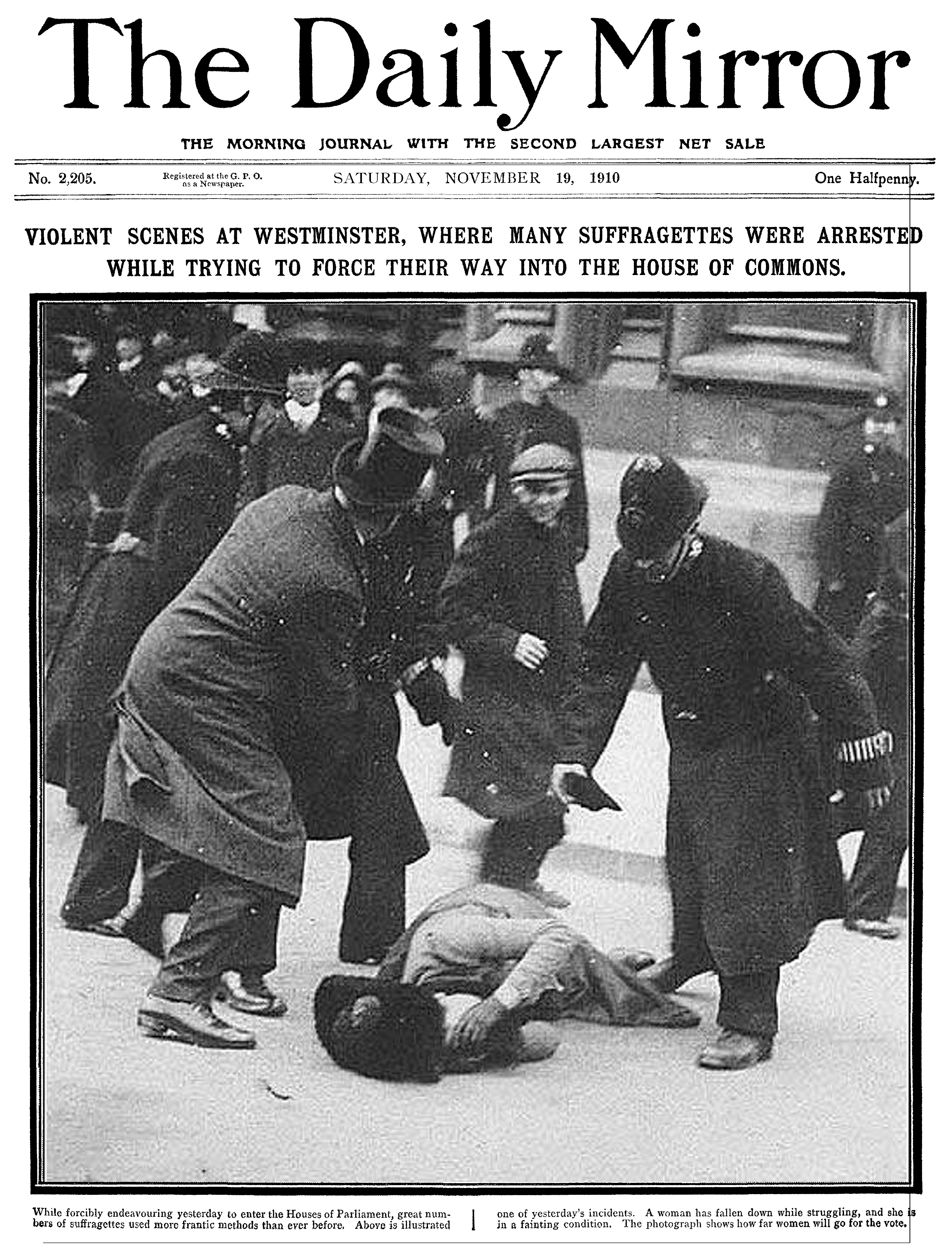

Black Friday

Mary attended the notorious ‘Black Friday’ events on 18th November 1910, where, over a six-hour period, 300 women outside Parliament were brutally beaten and deliberately sexually assaulted by uniformed and plain-clothed London police, almost certainly acting on Home Office orders. Mary was injured so badly she remained bedridden in Brighton for the next three days. It is probable she had experienced some form of head injury.

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence later wrote: “She could stand ill usage herself, but could not bear to see others victimised. The tears were streaming from her eyes as she watched the women flung like footballs between the police in uniform and the organised mob of roughs led on by plainclothes officers of the force.”

Mary’s friends, including the influential Louisa Martindale, were deeply concerned about her. They tried to dissuade her from leaving her sickbed, but on 22nd November Mary, despite her illness, returned to London with Minnie Turner to protest about the police’s actions.

When she heard others of the deputation had been arrested, including her sister Emmeline, she calmly and deliberately broke a police station window, her first illegal act. She said to the constable who arrested her: “I voted that the deputation should go, and am morally as responsible

as they are. If they are guilty of wrongdoing so am I, and I mean to share their punishment.”

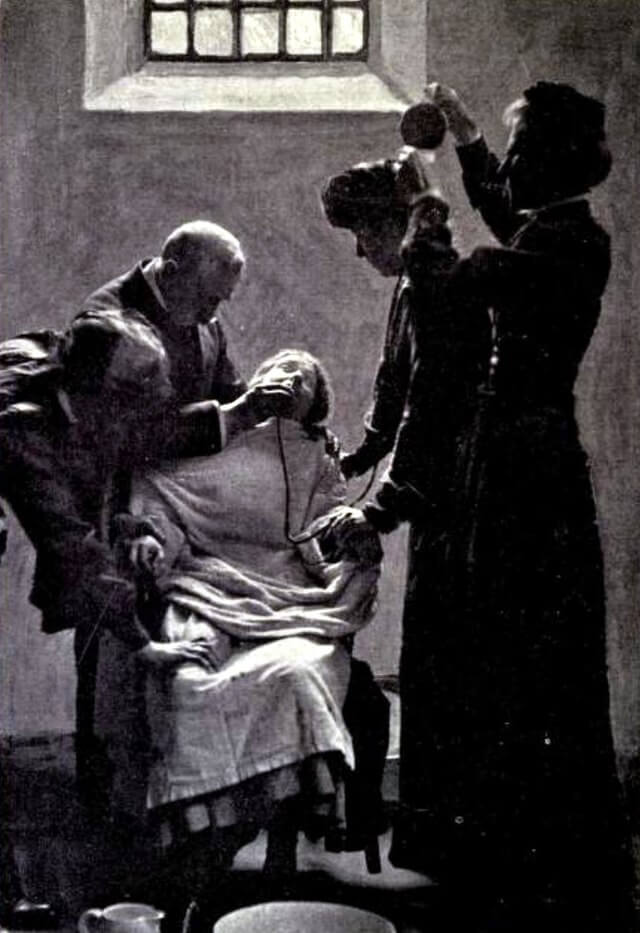

She was imprisoned for one month, her third and final period in gaol. She wrote to one of the friends who had tried to dissuade her from going for fear of further violence towards her: “I had to protest somehow; you would not have me a shirker.” When her sentence was pronounced she telegraphed to her Brighton members: “One month. I am glad to pay the price for freedom.” Despite her frailty, it is reported that when in prison Mary went on hunger strike and was forcibly fed. This cruel and illegal process caused terror, acute pain and often long-term injury to the women.

After her release from Holloway prison on 23rd December 1910, Mary attended a Welcome Meeting in London where, as Christabel Pankhurst reported, she made an inspirational speech. She then travelled to another Welcome Meeting in Brighton before returning to London to spend Christmas Day at her brother’s house.

Mary’s Death

Two days after release from prison, on Christmas Day 1910, Mary collapsed and died of a brain haemorrhage. She was buried quietly in a family plot in London. The Brighton branch of the W.S.P.U. sent a laurel wreath which was laid on her grave along with an embroidered banner. National headquarters sent a wreath of lilies and palms. John Clarke, the estranged husband to whom she was still legally married, inherited her small estate of sixty pounds.

Mary’s death was reported in newspapers across the country, but it never received the publicity of Emily Wilding Davison’s violent end under the King’s horse on Derby Day

1913. Nonetheless, her grief-stricken sister Emmeline, to whom she had been such a constant support, understood the political significance of her death. Two days after Mary’s death, she wrote an anguished letter to newspaper editor and former Liberal politician C.P. Scott calling Mary her “Dearest Sister” and saying: “She is the first to die. How many must follow before the men of your Party realise their responsibility.”

The deeply moving obituary for Mary, delivered by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence at

Mary’s memorial service in Brighton’s Royal Pavilion, referred to her as the “first woman martyr who has gone to death for this cause.”

Mrs Pethick-Lawrence recalled the graveside tribute to Mary sent by Brighton members: “Upon her last resting-place lies a laurel wreath, and upon it is inscribed those words which she telegraphed from the police court: ‘I am glad to pay the price for freedom’.”

At the Royal Pavilion memorial meeting, Isabella McKeown, a prominent Brighton suffragette, rallied the mourners saying: “Her they must not mourn in silence. They must take the torch from her and light the darkness of craft and cruelty.” That thought became the inspiration for the Mary Clarke Statue Appeal.

The Sculptor

The Appeal has commissioned the wellknown sculptor Denise Dutton, who made the statues of Annie Kenney in Oldham; the Landgirls and Lumber Jills at the national Arboretum; the Maharaja Duleep Singh in Thetford; and the statue of Mary Anning at Lyme Regis. She has completed a bronze maquette (model) made to the exact design of the proposed statue of Mary, as well as a resin copy. These are used for display and educational purposes. Once funding has been secured, the statue will be cast.

The Design

The Appeal is conscious of the cultural, educational and political significance of the proposed statue. We believe it will attract national and probably international attention especially given the lack of any other public memorial to Mary.

We asked the sculptor to design a realistic memorial, but one fit to symbolise the city’s historic and ongoing commitment to women’s rights, equality and democracy.

She was asked to tell the story of Mary’s life and sacrifice, to express her gentle dignity and strength as well as her courage and determination, hopefully inspiring others to live by her example.

Mary is depicted after leaving prison, two days before her death, gesturing towards a lamp at her feet which she has laid down for others to pick up. This recalls Isabella McKeown’s words at Mary’s memorial meeting in the Royal Pavilion: “Her we should not mourn in silence, but take up the torch and light the darkness …”. Her hand is held low, so that children can hold it and pose for photographs.

Mary wears a suffragette sash and on her left arm carries a last few copies of Votes for Women, the suffragette newspaper she regularly sold in Brighton. The front page of the November 1910 issue depicts the violent events of ‘Black Friday’, where Mary was injured.

She wears the Hunger Strikers’ medal and walks over the implements used in forcible feeding, which are imbedded in the surface of the plinth. Her clothing, accurate for the period, subtly references her background as an artist, her love of flowers and her time in prison. The prison arrows, which marked the Holloway Prison uniform, are incorporated in the dress design.

The low plinth carries Isabella McKeown’s words, quoted above, and those of Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence who called her “The first woman martyr to go to death for this cause”, as well as Mary’s own brave words: “I am glad to pay the price for freedom …”. Emmeline Pankhurst’s grief-stricken cry: “She is the first to die. How many must follow…” is on the surface of the plinth, curving around the feeding tube embedded in the bronze.

To make the it genuinely accessible, especially to children, the statue along with its low plinth will stand no taller than seven feet.

Possible Sites

Our key aim has been to find a well-lit, well-used, accessible and central site with a close historic link to Mary’s work, which residents and tourists, children and school parties can visit in safety, either individually or in groups. The hope is that the statue will tell Mary’s story and that this can be reflected by means of displays, information materials and exhibitions within nearby museums and historic and tourist venues, as well as further afield in local schools, colleges and universities.

We have explored several different sites. In her role as W.S.P.U. Organiser, Mary was active throughout the southeast, working both from the W.S.P.U. offices near the Clock Tower and from her lodgings at ‘Sea View’, the suffragette hotel at 13/14 Victoria Road. Mary regularly held meetings and sold the suffragette newspaper Votes for Women on the Brighton seafront, courteously addressing sometimes hostile crowds. She organised and addressed meetings at the old Hove Town Hall. All these could have been possible sites. However, since it was first agreed that Mary be commemorated, there has been general agreement amongst trustees, councillors and the community, that her statue should be placed “in or very near to the Royal Pavilion and Dome Estate”.

The Royal Pavilion and Dome Estate

The Estate has strong historic links with Mary and the suffrage movement. In 2018, the centenary of the first women achieving the Vote, The Dome was listed by Historic England as a site of National Suffrage Interest, because of the number of meetings and protests that happened there. The Royal Pavilion itself hosted public meetings of the suffragettes (Christabel Pankhurst spoke in the Music Room) as well as many ordinary business meetings of the W.S.P.U.. Mary’s own Memorial Meeting took place in the Royal Pavilion in January 1911, having originally been scheduled as a Welcome Meeting on her return from prison. The W.S.P.U. met in the elegant Pavilion creamery tea rooms (probably near the site of the present Pavilion Shop and tea room). There were also suffrage meetings in the Chapel Royal and in New Road Lecture Rooms and in Castle Square.

The initial preferred option of both trustees and supporters, was to place Mary’s statue in the Garden of the Pavilion and Dome Estate, near to the entrance to the Museum and the modern Educational Centre, where school parties pass and it could be easily and safely viewed and studied. However, this is a sensitive site and there were concerns that this might compromise the integrity of the Garden’s Regency design. As a result, the trustees have consulted widely and have agreed to propose another site, this time just outside the Gardens, in New Road.

Proposed New Road Site

The site we now propose is a highly visible one, very close to the Gardens, on the east side of New Road, directly opposite the Theatre Royal and within sight of The Dome and Royal Pavilion. New Road is

an historic thoroughfare, currently designated for shared use by pedestrians and some vehicles and visited by many thousands of people each year. The statue will be very visible at all times of the year and, if carefully lit, will look particularly beautiful at night, especially to audiences arriving at and leaving the Theatre Royal. The proposed site is accessible and close enough to the Museum and Garden entrances to allow school and student parties to visit. It is also in an area of highway designated for ‘street furniture’ not vehicle use. It is important to us that people of any age, whether residents or visitors, including those with disabilities, should be able to visit and study the statue, film it and take photographs, in complete safety.

Landscaping and planting

This site offers limited opportunities for landscaping and planting. However, there may be potential for structures and plants that both frame and protect the statue, while subtly referencing Mary’s life and suffrage history. We know that over the next few years, as a part of its ambitious plans for regeneration, the Pavilion Gardens are to be surrounded by iron railings, which will provide an impressive backdrop to New Road and, we hope, the statue. Few suffragettes chained themselves to railings, but nonetheless the image of a suffragette statue near to railings is bound to resonate.

The suffragettes were very conscious of the symbolism of plants and of biblical and classical associations. The flowers most associated with Mary are irises, which she loved and used to paint. At Mary’s funeral the floral tribute from the national W.S.P.U. headquarters was made of lilies and palms, the lilies suggesting purity, the palms sacrifice, both often used in suffragette processions.

We hope to plant a laurel somewhere near the statue. Laurel was recognised by the suffragettes to be a symbol of victory and heroism and would also recall the laurel wreath laid on Mary’s grave by the Brighton branch of the W.S.P.U.. Another possibility would be holly, often used to symbolise sacrifice, and particularly apt considering Mary’s death on Christmas Day. Yet another would be rosemary, for remembrance. Planting might also subtly reflect suffrage colours of white, green and deep plum/purple. We will consult with the City Council and Royal Pavilion and Museums Trust, as well as the Pavilion Gardens Cafe, about whether appropriate planting, behind the new railings, just within the borders of the Garden, might be possible. A dwarf cedar might be particularly appropriate.

Commemorative Cedars

W.S.P.U. members planted a Suffrage Arboretum in Batheaston in honour of prominent suffragettes – often called Annie’s Arboretum after its founder, leading suffragette Annie Kenney. A Himalayan Cedar was planted in Mary’s memory by Annie Kenney on 15th January 1911, the plaque saying In Memory of Mary Clarke, released from Holloway Prison 23rd December 1910, died 25th December 1910. Emmeline Pankhurst later chose the same species of cedar as her own tree.

Here again, symbolism mattered. The suffragettes tended to plant cedars for leaders who had endured much for the cause. They would have been well aware of the tree’s biblical association with strength and incorruptibility, endurance and immortality. They probably did not know that the deodar (or devadaru) was introduced to Britain from India just after the Regency period or that it means ‘wood of the gods’ in Sanskrit. However, this is of interest to us, given the Pavilion Estate’s links with India.

The Arboretum, which commemorated so many prominent suffragists (one tree for each woman), was destroyed in the 1960s, to build a housing estate. Only one tree survives. However, there are efforts elsewhere in the country to re-plant these memorial trees. The Appeal hopes to work with the City Council to plant at least one memorial cedar, if not near to the statue, then somewhere in the city centre.

Education and Community Impact

Our campaign has never just been about achieving a beautiful artwork. We intend the statue, like the resin maquette and model lamp we already display in schools and community settings, to inspire people and to demonstrate the importance of equality, women’s rights and democracy – in particular the right of all people to exercise democratic choice without fear of violence. The statue is intended to provide a model of female courage and political leadership, encouraging children and adults to participate in civic life, fostering a better understanding of women’s history and the struggle for democracy.

We work with community groups and have piloted work with schools, appointing Child and Youth Ambassadors who, inspired by Mary, have acted as valued volunteers. They have raised awareness in their communities, made presentations to politicians, fundraised and been interviewed by the media. Some set up a pilot ‘Mary’s Lamp’ girls’ group in a local primary school, work we hope to continue.

We currently display our bronze maquette, made to the design of the proposed statue, in Brighton’s Jubilee Library.

The Future

We have raised £20,000 of the £60,000 we need to complete the statue. The trustees had hoped to reach our target by July 2023. However, fundraising was stalled by Covid and then the cost-of-living crisis. The Appeal is determined to have the statue in place, ideally by 2026 and certainly by the important 2028 Centenary of the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928, which enfranchised all women.

The Appeal is grateful to have all-party support from the City Council and the backing of local members of Parliament as well as distinguished patrons and ambassadors. Our charity will work with the Council to ensure that, in advance of the 2028 Centenary, our city benefits from anticipated national government grant aid and that Brighton and Hove is recognised as the important ‘Suffrage City’ it is.

Appendix

The Utmost for the Highest – A Memoir by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence

The following Eulogy for Mary Clarke was delivered by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, one of the national leaders of the W.S.P.U., at the Memorial Meeting for Mary held on 6th January 1911 at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton. It was published in Votes for Women dated 6th January 1911.

“Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friend.” Mary Clarke laid down her life for the most deeply wronged, the most cruelly bound of all the human race. She died for those women numbered in this land of ours, and in all lands of the Earth, by the thousand thousand; women to whom death would be merciful, so cruelly used have they been by man and by man-made law. These defenceless and voiceless ones were “her friends”. Because of the great compassion for them that was in her heart she faced ridicule, blows, brutal usage by roughs, the handling of the police, and three imprisonments. For them she paid (to use her own words) “the price of freedom”. Glad to pay it – glad though it brought her to her death.

I vividly remember seeing her suddenly in prison. She had gone with two or three others to knock at Mr Asquith’s door. Some weeks later I was myself arrested for attempting to take a petition to the House of Commons, and went for two months to Holloway Gaol. On the first morning I heard a low voice speaking my name. I turned round, and it was some seconds before I recognised her in the disfiguring criminal garb. It seemed to me especially shocking to see that frail, refined, sensitive woman, clad in so coarse and grotesque a way, “numbered” amongst the depraved, for, of course, she was wearing the prison badge. Her face wore that look of extreme patience and extreme gentleness which was it’s habitual expression in repose. In that dreary place of despairing souls she seemed indeed a “Prisoner of Hope”.

It was her second imprisonment. The first time she had been arrested as a member of the deputation that sought to interview the Prime Minister in the “People’s House“. For the third and last time she endured that experience which, as she expressed it in her speech two days before she passed from us, stamped fast and indelible the “purple, white and green” upon the soul of every woman who went through it. She referred to herself as dyed, double-dyed and thrice dyed a suffragette by the baptism of imprisonment.

Beside that vision of Mrs Clark in prison I have another specially clear remembrance of her. This was at the first informal meeting of the W.S.P.U. in London, February, 1906, when we originally formed a London committee. Mrs Pankhurst was there, Mrs Drummond, Sylvia Pankhurst, Annie Kenney, Mrs Clarke and one or two others beside myself. From that little meeting the entire Movement in London and the entire National Movement sprang and developed. During all those years Mrs Clarke has been identified with it.

She was naturally so quiet, so shrinking that, when the way cleared for her to devote her whole time to the work and when the post of Organiser was offered to her, she could not believe that she would be able to fulfil the onerous duties of leadership. She quickly became a remarkably successful organiser, winning the love and confidence of members wherever she went, inspiring courage and devoted service, dominating the rough elements that are always found in election crowds, quelling the brutality of Liberals of a baser sort, roused to fury by party fanaticism as they realised the damage done to their side by her lucid argument and persuasive speech.

In that frail and delicate woman’s body there was an indomitable spirit and courage past belief. No stress of weather, no intimidation or actual violence could deter her. She would hold at election times and at other busy seasons, three or four open-air meetings a day, day after day, standing in the rain so long as people would listen. A Brighton member writes that once a mob of young men surrounded her and refused to let her past. She reasoned with them at first, but when she saw they were determined to detain her she began to read her paper Votes For Women as if she had been in a drawing room. Seeing her so indifferent and unperturbed the youths got tired of this noble sport of womanbaiting, in which they have been so conspicuously encouraged by those in high places, and slunk away in small groups.

She was on several occasions very much knocked about, and some of her young workers were inclined to strike out in her defence, but she always restrained them. A Brighton member writes: “Once some roughs tried to pull me off the van by my coat, and I wanted the whip to hit them off, but she would not let me have it, offering to change places with me. Of course I refused.“

We extract from an appreciative article in the Sussex Daily News a testimony to her habitual sweetness of temper: “Her ability as a speaker is well known by the hundreds who have listened to her earnest addresses on the Front, for she was the most indefatigable organiser of the Brighton Branch of the W.S.P.U. Of heckling Mrs Clarke could stand a great deal. Though jeered at, mocked and ridiculed, her face wore always a sweet smile, and she was quite ready and willing to answer any reasonable questions put to her.” “She realised one’s ideal of courage and gentleness,“ writes one of her workers.

Mrs Clarke was greatly distressed by the terrible scenes she witnessed on Black Friday. She could stand ill usage herself, but could not bear to see others victimised. The tears were streaming from her eyes as she watched the women flung like footballs between the police in uniform and the organised mob of roughs led on by plainclothes offices of the force. She determined there and then to take part in any further action that might be necessary. But she became ill on her return to Brighton, and was obliged to keep her bed all the following Sunday and Monday. Her members implored her not to come up on the Tuesday. At last she promised one who loved her with great and special tenderness that she would not run the risk of being knocked about, but would choose another method of making a protest against the way the deputation had been treated. When she heard that the Tuesday deputation had been arrested she said, “Prison is the only place for self respecting women”. She calmly put a stone through the window of the police-station, saying to the constable who arrested her, “I voted that the deputation should go, and am morally as responsible as they are. If they are guilty of

wrongdoing so am I, and I mean to share their punishment.“ She wrote to the friend who had implored her not to expose herself to violence, “I had to protest somehow; you would not have me a shirker.“ When her sentence was pronounced she telegraphed to her Brighton members, “One month. I am glad to pay the price for freedom“. In her letter to them from prison she said, “At 9 o’clock every night I shall be singing ‘To Freedom’s Cause Till Death’.”

The price has been paid – paid to the full. Mrs Clarke is the first woman-martyr who has gone to death for this cause. And quickly upon her footsteps has followed Henria Williams, another victim of Black Friday. How many more lives must be laid down, how many more of the best and noblest of the daughters of the people will be sacrificed before an elementary act of justice and reparation is done to the womanhood of the country? There will be no holding back of the women of this Union. Inspired by the example of our “saints“ there will be an eager desire to press forward, cost what it may. One letter is typical of the general feeling that animates the Union: “Somewhere I’ve read that ‘we mourn best when we do what the dead desire.’ I wish to go on the next deputation.“

“The last thing we did“ writes one of her fellow prisoners released earlier, “when we left Holloway was to call up ‘Good luck and goodbye’ to her window. She has had good luck, for death has honoured her.“ “I grieve with you,“ says another member of the last deputation. “I would that a worn out brush like myself might have paid the price.“ “Her work is by no means done.“ Another writes, “By her example many others will try to follow in her footsteps.“ Again and again recurs in the letters received at headquarters the acknowledgement “We realise that she literally laid down her life.” From Ireland comes a letter from one who was released with Mrs Clarke: “In ancient Ireland the monument to the beloved and respected dead was made by the friends bringing one stone each to the mound, and the size of the accumulated pile showed the number of the friends. Truly, did ancient custom prevail amongst us, her cairn would rise like unto one of those hills ‘from which cometh our strength’.”

A working girl sends a verse from (“Poems by the Way”) William Morris:

“Here lies the sign that we should break our prison,

Amid the storm she won a prisoner’s rest,

While in the cloudy dawn the sun arisen

Gives us our day of work to win the best.”

On the day of her release from Holloway Prison she spoke, with eyes shining with happiness, of her joy in the welcome given to her and those with her, adding, “If only it were not for the thought of those we have left behind!“

I remembered those words as I stood with the mourners at her grave side. Again she had found the joy of release. She had passed now and for ever out of the human power of those who hate Justice and keep Liberty in chains. Was the joy of her free spirit touched with sorrow for us whom she had “left behind“?

We may be sure that those whom she left in prison, who are still in prison and will be for many days to come, have no thought of pity for themselves. They have their work to do “to win the best“.

That thought is our inspiration also. Writing from prison to a girl whose youth prevented her from taking part in militant work, she said: “I wish you would hold a meeting on the Front as my deputy. Never mind about being too young. Tell them that while the old are in jail the young ones must do their work.“ The spirit of that instruction is the spirit of Mrs Clarke‘s message to young and old in this Union. Those who have held aloof hitherto or have refused the ultimate sacrifice must come forward now as her “deputy“.

Upon her last resting-place lies a laurel wreath, and upon it is inscribed those words which she telegraphed from the police court: “ I am glad to pay the price of freedom.“ This was sent as a tribute from the Brighton members. Upon a wreath of lilies and palms sent by the members of the Headquarters Committee, were the lines:

“The Spring will come, though we must pass Who gave the promise of its birth.”

There was no singing at the grave side, for owing to the breakup of the holidays the funeral was private, and but few were able to be present.

I would that we could have sung our marching song:

To Freedom’s Cause till death

We swear our fealty,

March on, march on! Face to the Dawn,

The Dawn of Liberty.

Also the one and only hymn adequate to the occasion – the Church’s victory song:

Oh blest Communion! Fellowship Divine,

We feebly struggle, they in glory shine,

Yet all or one in Thee, for all are Thine,

Alleluia.

She is the first to die. How many must follow …?

Emmeline Pankhurst

… her we should not mourn in silence, but take up the torch and light the darkness …

Isabella McKeown